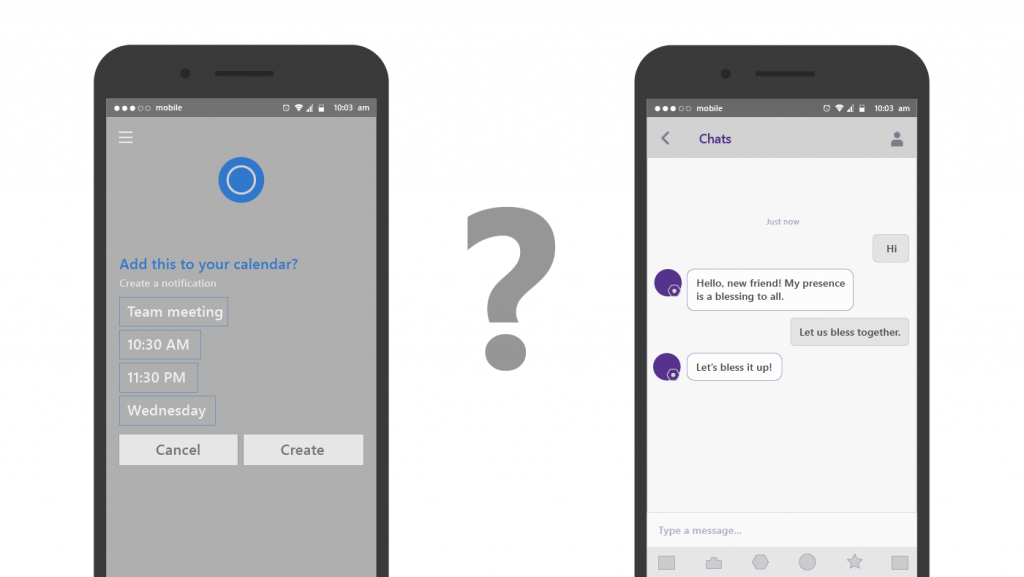

Chatbots come in many flavors, but most can be placed in one of two categories: goal-oriented chatbots and chit-chat chatbots. Goal-oriented chatbots behave like a natural language interface for function calls, where the chatbot asks for and confirms all required parameter values and then executes a function. The Cortana chat interface is a classic example of a goal-directed chatbot. For example, you can ask about the weather for a specific location or let Cortana walk you through creating a new calendar entry.

Chit-chat bots primarily keep the user engaged. This can involve throwing in random trivia, puns, or even memes. These bots often artfully avoid going into depth on any specific topic; their conversation has no goal other than maintaining the conversation itself.

PODCAST SERIES

Most conversations operate somewhere between the two chatbot types. For example, when we talk to a person to get a recommendation, we expect that person to get to know us a bit before making a suggestion. A recommender you’d trust does more than just check boxes; he or she establishes trust by demonstrating a level of knowledge on a topic, but the exchange should still have a clearly defined topic and goal.

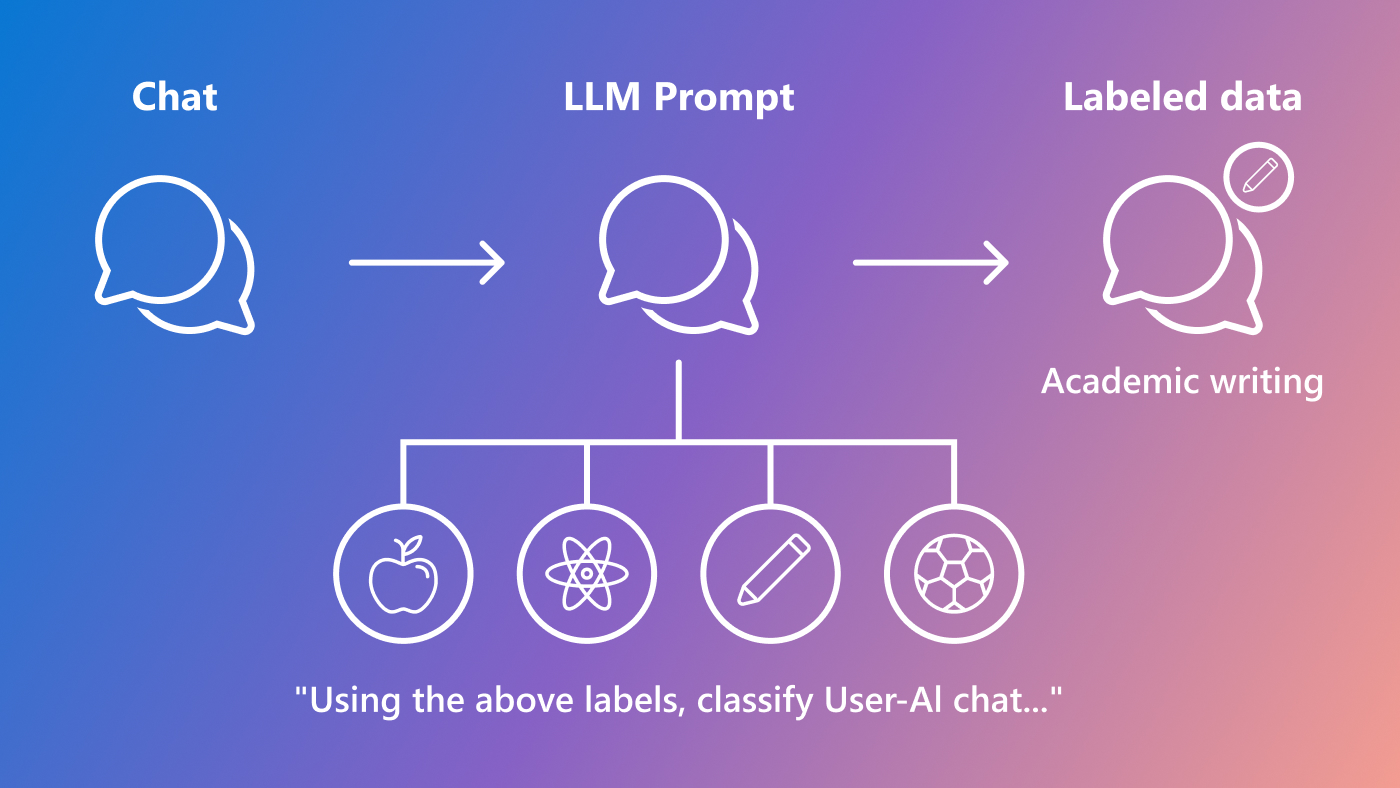

To study this setting—named conversation recommendation—a team of researchers working at Polytechnique Montréal (opens in new tab), Mila – Quebec AI Institute (opens in new tab), Microsoft Research Montréal, and Element AI (opens in new tab) collected a dataset of more than 11000 dialogs (opens in new tab) based on crowd workers recommending movies to each other. The researchers used a trick to simultaneously collect labels, asking the crowd workers to tag all movie mentions in their dialogues using a dropdown search that appeared when the worker typed the `@’ character. In a questionnaire following the dialogue, both participants were asked questions about the @-mentioned movies, on which the participants had to agree. This cross-checked self-labeling resulted in high-quality labels for the dialogues that the researchers then used to train the components of a chatbot.

In their baseline model, the “social” component is covered by an extension of the popular hierarchical recurrent encoder-decoder (HRED) model, whereas the recommendation engine is a denoising auto-encoder pretrained on the MovieLens dataset (opens in new tab). A recommendation engine typically suggests movies based on the previous preferences of its users. The researchers leveraged the collected labels to train a sentiment analysis mechanism that predicts how much the recommendation seeker liked a mentioned movie from the dialogue. This constitutes a novel form of sentiment analysis, because in contrast to, say product reviews, the sentiment in a dialogue can be expressed in question/answer form over multiple speaker turns.

Finally, both systems can be combined by learning a “gating” mechanism in the decoder of the HRED model. The gate decides whether to output a word from the chatbot vocabulary or a movie title taken from the recommender.

While their baseline implementation is by no means perfect, it highlights the possibilities and challenges arising from the dataset collection scheme. Future models will profit from incorporating question-answering mechanisms and external data sources into the model to support conversations about actors, movie genres or topics. The recommender module will improve by, in addition to ratings, taking the expressed preferences (which could be very much mood-dependent) into account.

The research paper will be presented at this year’s NeurIPS (opens in new tab) conference. You can find it and the dataset at the project’s website (opens in new tab).